Most Lean folks use “5-Whys” daily to problem solve; but, relatively few are familiar with a clever problem solving device developed 30 years ago by Deming Prize winner,

Ryuji Fukuda, called the Why-

Not Diagram.

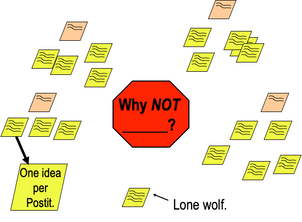

Because objection is a natural human response to new ideas, Dr. Fukuda created the Why-Not Diagram to afford every stakeholder an opportunity to put his or her concerns out on the table: all the reasons why an idea

won’t work. Fukuda recommends that why-not reasons be recorded in silence so that no one is unduly influenced by anyone else. We use a separate post-it note for each separate idea. In my own experience, this technique generates a lot of post-it notes. It seems to be easier for participants to fire off thoughts about why something

won’t work than how it will work.

Some time ago, my previous company was having an especially tough sales quarter and the level of frustration was high throughout the organization. I posed this Why-Not question to my field sales force:

“Why Not Double Sales?” In a cathartic burst, our sales people busily wrote all the reasons they could think of as why our sales were low: late delivery, billing issues, bad sales policies, too many reports, slow response to questions, long time to market for new products, etc. Some had very specific causes, while others were more general, but all were recorded in silence over a period of about twenty minutes and passed to me. Then we read the notes aloud, one-by-one, and organized them by category, creating an affinity diagram of why-nots. Clear categories emerged as we continued reading; and there were many duplicates, which we piled on top of one another creating a visualization of consensus. Finally, there were a couple of post-its that didn’t fit into any category. “Lone Wolves,” Dr. Fukuda calls them; things that most persons had not previously considered. One note turned out to be a brilliant and previously missed issue with our sales process. As that Post-It was read, there was a quiet murmur in the room acknowledging that in the process of collecting our thoughts, something new and special had been discovered.

As the salesperson team was congratulating themselves for a concerted show of resistance to the idea of doubling sales, I challenged them: “So what I take from this exercise is that if we can address all of these objections, then we CAN double sales.” A couple of startled participants protested. “Oh no, we didn’t mean to imply that.” After a few moments of silence however, another participant thoughtfully replied, “Well . . . maybe.” The seeds for change had been sewn.

From this experience I take two lessons which, particularly in this chaotic and emotion-charged pandemic time are worth relating:

The first lesson is from one of my favorite stimulators,

Alan Watkins. creator of

Crowdocracy, Watkins asks “Who is the smartest person in the room?” The answer is...

ALL OF US. The collective intelligence of everyone easily surpasses that of any single person. This concept is not new to Lean (“The ideas of 10 are greater than the experience of 1.”), but it is not well practiced. Fukuda’s Why-Not gets everyone involved; it’s a trick to surface objection and create dialogue. If we have conflicting views about how to adapt to Covid-19, we should share them – maybe there will be lone wolf or two.

The second is from Shigeo Shingo who said “99% of objection is cautionary,” meaning that when persons express objections to an idea, they are often saying they don’t agree YET. They need more information. From my days in sales promotion I recall that every sale begins with “no.” Getting these ‘no’s’ out into the open, rather than letting them privately fester, is the first step to responding to them. Dialogue is the countermeasure to objection. Let’s keep it going.

Stay safe everyone.

O.L.D.