A Blog About Understanding The Toyota Production System and Gaining Its Full Benefits, brought to you by "The Toast Guy"

Strategy Digi-deployment

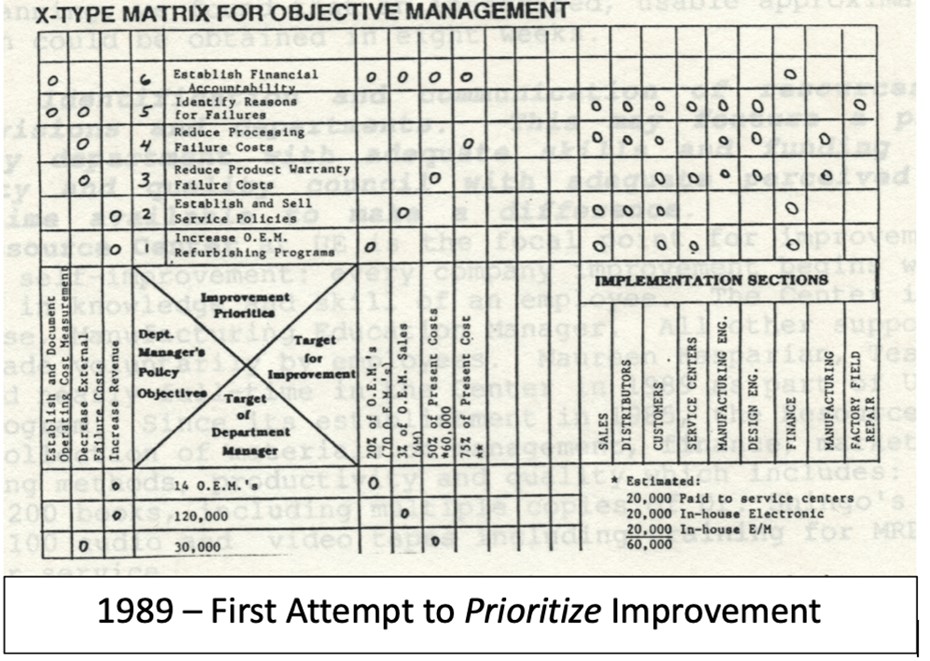

Deming Prize winner, Ryuji Fukuda, introduced a document to my company in 1989 referred to as the X-Type Matrix for Objective Management. Relatively unknown at the time, it’s since become a popular format for strategy deployment. Named for the X format that connects strategic (3-5 years) objectives to tactical improvements, measures and annual targets, its purpose, as Dr. Fukuda explained, was to clarify an organization’s strategic direction and then create vertical and horizontal alignment and resourcing for a carefully chosen set of improvement priorities.

Before we discovered the

Before we discovered the

X-matrix, my company was chasing problems in an ala carte fashion I described in a 2011 post, drowning in opportunities. Our point solutions at the time could be described as whack-a-mole, utilizing tools from the Toyota House, but unconnected to a clear vision. The X-matrix forced us to make choices to deploy scarce resources to a few critical improvement efforts. It was a contract, as much about what was NOT important as what was; one that focused on systemic change rather than localized improvement. Moreover, Dr. Fukuda counseled that managers should work together to keep the list of tactical improvement priorities at no more than eight! (I recall that our initial list of priorities included several dozen projects, all competing for the same resources.) That constraint was, in fact, the biggest challenge and also the biggest breakthrough, forcing managers to work through silos for a higher purpose. Working together like this was new to us. There were a lot of erasures on the page and much initial angst from managers concerned that their pet projects would be forgotten. During our training, I questioned Fukuda about selecting the improvement priorities: “How do we decide which are the critical few priorities?” Fukuda answered, “You are the managers. It’s your job to decide.” Ultimately, we did decide on a doable list that created alignment.

Fast forward 35 years, that challenge for managers to decide is still the same. The image of the Toyota House describes remarkable techniques that will reduce waste and solve problems; but there is no hint from that model which problems to solve first. And the silos are also still there.

What has changed since 1989 is the means by which the X-matrix is constructed. Excel, barely a baby in 1989, has developed into a powerhouse simulation tool, complete with nested bowling charts, A3’s, trending and digital scoreboards. From a technical point of view the process is far superior to the sheet of paper distributed by Ryuji Fukuda. Digitization of strategic deployment, however, presents a few potential (and common) pitfalls to avoid:

- The fact that Excel will accommodate over one million rows does not mean there can be more than eight improvement priorities. Today, as in 1989, too many priorities equals no priorities. The hard work to decide is still necessary.

- Excel’s inherent capability to support complex matrices can create an unproductive fascination with technology. Managers should provide systems that people can understand and use. The purpose of the X-matrix - vertical and horizontal alignment – can be lost in tabs and links that only the geeks understand. Simpler is better.

- Beware the apparent legitimacy of digitization. Managers are responsible to create a strategy that can actually be deployed, not one that looks good. In Dr. Fukuda’s words “Don’t make it pretty. Make it right.”

How effective is your strategic planning process. Is it driving the important improvements? Are you avoiding the pitfalls? I'd love to hear from you.

O.L.D.

By the way. I’ll be presenting the Shingo Institute’s ENTERPRISE ALIGNMENT workshop - in person, at Osram Automotive in Hillsboro, New Hampshire - on April 16 and 17. There’s still time to register. Here’s the link to REGISTER.

By the way. I’ll be presenting the Shingo Institute’s ENTERPRISE ALIGNMENT workshop - in person, at Osram Automotive in Hillsboro, New Hampshire - on April 16 and 17. There’s still time to register. Here’s the link to REGISTER.

Also, Larry Anderson and I will be presenting a half-day seminar on May 9 at the 36th Annual Shingo Conference in Orlando, Florida. Click here to learn more about our exploration of the topic “Shingo’s Kata: STM.”