A Blog About Understanding The Toyota Production System and Gaining Its Full Benefits, brought to you by "The Toast Guy"

The Power of Commitment

As promised in my last post, here is another tribute to Mr. Hajime Oba:

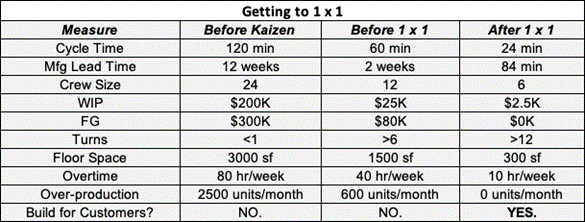

In 1996, TSSC (Toyota Production System Support Center) began working with my company to create one-by-one production capability in our product assembly. Previous to TSSC’s assistance we’d moved the furniture and machines into cells creating the appearance of flow production, but we lacked the problem-solving know-how and management discipline to create real flow. Remarkably, after several months of focusing on our pilot line, it appeared that all of the pieces of the puzzle had been identified and matched, and that impediments to flow had been remediated. Our Kaizen support team and assemblers had worked daily to simplify, standardize, levelize, balance and mistake-proof assembly operations. Conveyance routes were also standardized, providing material just-in-time at a rate of three kits every twelve minutes to match a customer takt time of four-minutes per assembly. It was now time for our first live trial of a full production day with a production goal of one product every four minutes – or 120 products by day’s end.

Background. As an organization that had only several years earlier produced to stock in batches five to ten times greater than customer need, this trial run was a remarkable and exciting milestone. We had previously been, as we joked, “the kings and queens of over-production”, always busy expediting to fill customer stockouts. Over-production, sometimes referred to as the worst of the 7 wastes because it creates more of the other six, had once been viewed by us as a hedge against long lead-times. Now, however, we’d become aware that excess production was actually the cause. Little by little, with daily Kaizen, we’d whittled down the production queues from twelve weeks to two-weeks.

Commitment. Then we requested and received TSSC’s assistance. “We’re satisfying customers’ delivery requirements now,” I told Mr. Oba, TSSC’s General Manager, “but only through excessive overtime.” Observing the process, Mr. Oba responded, “TSSC will assign a consultant to assist you to address your overtime condition.” “Great,” I said, what do we need to get started?” “Commitment!” Mr. Oba said. “Our role at TSSC is to provide information and inspiration to your team, and your role is to be committed to improvement.” Not entirely clear on what I was agreeing to, I nevertheless nodded affirmatively.

New Lenses. Working under the guidance of a consultant from TSSC, we (and I) found the process of surfacing and removing problems with flow both energizing and exhausting. The assemblers emerged as stars – the real knowledge workers. The rest of us were there to support. So many “little” problems surfaced every day, and every day we did our best to remove them. This, I think, was the commitment that Mr. Oba was referring to. A key learning point for me was that commitment requires understanding; the more I understood, the more committed I was to improvement.

Hypothesis. During this focus on our model line, we kept extra resources available – people and inventory – to meet customer demand. Experiments or tinkering that occurred on the model line could not adversely affect customer service. So, up until our full-day go-live trial, everything was still a hypothesis. As a hedge for our pilot, we scheduled a full-day on Saturday to “get the kinks out.” On Friday night, we set up the line with a mixed-model sequence list levelized for best flow, and standard work in process levels for one-by-one assembly. The inventory safety net was removed. Nevertheless, I was confident that we would execute one-by-one production, in sequence, at about 80% of plan. I envisioned a carefully choreographed flow of material, smooth hand-offs and quick remediation of problems. Our assemblers were less optimistic.

The Big Day. On Saturday morning, with a full assembly crew and support functions we set out to test our hypothesis. To this point we had operated with the protection of excess inventory between operations; now there was just one piece of standard work in process between assemblers. As the test began, we watched with anticipation. Work was balanced and assemblers were experienced; what could go wrong?

“Wrong part” declared the group lead, Jose L. about nine minutes into the day. The line stopped for three minutes while we searched for and replaced the part. During the day, the same problem recurred with other parts. Each time, as the line stopped, the assemblers grew more agitated. Next there were problems with information. Jose showed me, “The customer drawing does not agree with ours.” Then the order of jobs on the in-chute did not agree with the sequence list the assemblers were to follow. The list of problems grew faster than the rate of production. Missing parts, defective parts, tolerance issues, mistakes, computer glitch, broken tool. We stopped each time to try to solve problems, but not all could immediately be traced to root cause, and for each problem solved it seemed that two more were discovered.

Moment of Truth. By day’s end, after eight-hours of production, out of one-hundred and twenty products planned for assembly, only seventeen had been produced. One assembler commented, “This the worst system ever. Anytime something goes wrong, we all stop.” Another declared “We knew this was going to happen; so many little things go wrong and there’s just no way to keep assembling without a few pieces of extra stock.” Then the material handler spoke up: “You know, because of all the extra material you have squirreled away, most of the problems with parts delivery were invisible to me until today. Harvey C, former factory foreman and now a member of our Kaizen support team, chimed in. “Our problem is not that we can’t fix problems. It’s that with all the inventory protection we haven’t been able to see all of them.” I agreed. “We learned more today about problems with our process than in the previous three months. We’ve got keep moving forward.”

Consequences. The list of problems we discovered that Saturday was not only huge, it was also just the beginning of discovering delays that were only visible during one-by-one production. Every day for the weeks thereafter we battled new problems, inching toward the goal of one-by-one production that Mr. Oba had assured me would occur if we showed a commitment to continuous improvement. After six weeks, we hit the production goal along with other significant improvements to productivity. But, more than that, we had developed a broad enthusiastic base of problem surfacers and solvers: everybody, everyday.

O.L.D.

BTW – Hope you can make my monthly Teatime with the Toast Dude webinar tomorrow, November 16, at 3:00 p.m. Topic is “The Many Faces of Kaizen.” It’s free. Here’s the link to reserve your seat.

And please check out our upcoming GBMP and Shingo Institute workshops at www.shopgbmp.org. 2022 is almost here. Time to re-energize your commitment to Kaizen.